Proper time

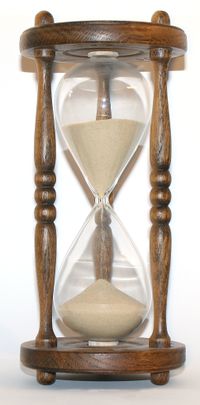

In relativity, proper time is time measured by a single clock between events that occur at the same place as the clock. It depends not only on the events but also on the motion of the clock between the events. An accelerated clock will measure a proper time between two events that is shorter than the coordinate time measured by a non-accelerated (inertial) clock between the same events. The twin paradox is an example of this effect.

In terms of four-dimensional spacetime, proper time is analogous to arc length in three-dimensional (Euclidean) space. By convention, proper time is usually represented by the Greek letter τ (tau) to distinguish it from coordinate time represented by t or T.

By contrast, coordinate time is the time between two events as measured by a distant observer using that observer's own method of assigning a time to an event. In the special case of an inertial observer in special relativity, the time is measured using the observer's clock and the observer's definition of simultaneity. A Euclidean geometrical analogy is that coordinate time is like distance measured with a straight vertical ruler, whereas proper time is like distance measured with a tape measure. If the tape measure is taut and vertical it measures the same as the ruler, but if the tape measure is not taut, or taut but not vertical, it will not measure the same as the ruler.

The concept of proper time was introduced by Hermann Minkowski in 1908.[1]

Contents |

Mathematical formalism

The formal definition of proper time involves describing the path through spacetime that represents a clock, observer, or test particle, and the metric structure of that spacetime. Proper time is the pseudo-Riemannian arc length of world lines in four-dimensional spacetime.

From the mathematical point of view, coordinate time is assumed to be predefined and we require an expression for proper time as a function of coordinate time. From the experimental point of view, proper time is what is measured experimentally and then coordinate time is calculated from the proper time of some inertial clocks.

In special relativity

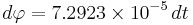

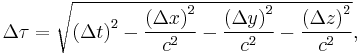

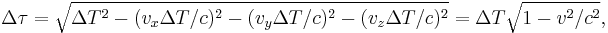

In special relativity, proper time can be defined as

where v(t) is the coordinate speed at coordinate time t, and x, y, and z are Cartesian spatial coordinates.

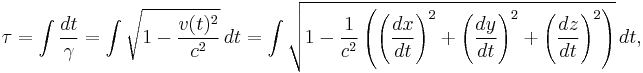

If t, x, y, and z are all parameterised by a parameter λ, this can be written as

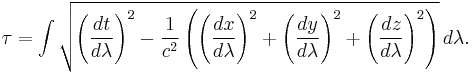

In differential form it can be written as the line integral

where P is the path of the clock in spacetime.

To make things even easier, inertial motion in special relativity is where the spatial coordinates change at a constant rate with respect to the temporal coordinate. This further simplifies the proper time equation to

where Δ means "the change in" between two events.

The special relativity equations are special cases of the general case that follows.

In general relativity

Using tensor calculus, proper time is more rigorously defined in general relativity as follows: Given a spacetime which is a pseudo-Riemannian manifold mapped with a coordinate system  and equipped with a corresponding metric tensor

and equipped with a corresponding metric tensor  , the proper time

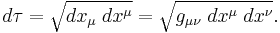

, the proper time  experienced in moving between two events along a timelike path P is given by the line integral

experienced in moving between two events along a timelike path P is given by the line integral

where

Derivation

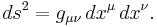

For any spacetime, there is an incremental invariant interval ds between events with an incremental coordinate separation dxμ of

This is referred to as the line element of the spacetime. s may be spacelike, lightlike, or timelike. Spacelike paths cannot be physically traveled (as they require moving faster than light). Lightlike paths can only be followed by light beams, for which there is no passage of proper time. Only timelike paths can be traveled by massive objects, in which case the invariant interval becomes the proper time  . So for our purposes

. So for our purposes  .

.

Taking the square root of each side of the line element gives the above definition of  . After that, take the line integral of each side to get

. After that, take the line integral of each side to get  as described by the first equation.

as described by the first equation.

Derivation for special relativity

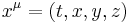

In special relativity spacetime is mapped with a four-vector coordinate system  where

where

- t is a temporal coordinate and

- x, y, and z are orthogonal spatial coordinates.

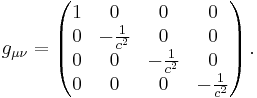

This spacetime and mapping are described with the Minkowski metric:

(Note: The +--- metric signature is used in this article so that  will always be positive definite for timelike paths.)

will always be positive definite for timelike paths.)

In special relativity, the proper time equation becomes

as above.

Examples in special relativity

Example 1: The twin "paradox"

For a twin "paradox" scenario, let there be an observer A who moves between the coordinates (0,0,0,0) and (10 years, 0, 0, 0) inertially. This means that A stays at  for 10 years of coordinate time. The proper time for A is then

for 10 years of coordinate time. The proper time for A is then

So we find that being "at rest" in a special relativity coordinate system means that proper time and coordinate time are the same.

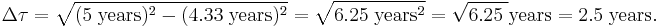

Let there now be another observer B who travels in the x direction from (0,0,0,0) for 5 years of coordinate time at 0.866c to (5 years, 4.33 light-years, 0, 0). Once there, B accelerates, and travels in the other spatial direction for 5 years to (10 years, 0, 0, 0). For each leg of the trip, the proper time is

So the total proper time for observer B to go from (0,0,0,0) to (5 years, 4.33 light-years, 0, 0) to (10 years, 0, 0, 0) is 5 years. Thus it is shown that the proper time equation incorporates the time dilation effect. In fact, for an object in a SR spacetime traveling with a velocity of v for a time  , the proper time experienced is

, the proper time experienced is

which is the SR time dilation formula.

Example 2: The rotating disk

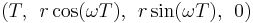

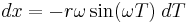

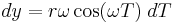

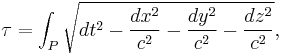

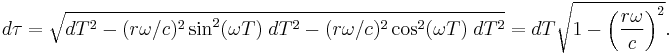

An observer rotating around another inertial observer is in an accelerated frame of reference. For such an observer, the incremental ( ) form of the proper time equation is needed, along with a parameterized description of the path being taken, as shown below.

) form of the proper time equation is needed, along with a parameterized description of the path being taken, as shown below.

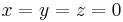

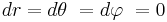

Let there be an observer C on a disk rotating in the xy plane at a coordinate angular rate of  and who is at a distance of r from the center of the disk with the center of the disk at x=y=z=0. The path of observer C is given by

and who is at a distance of r from the center of the disk with the center of the disk at x=y=z=0. The path of observer C is given by  , where

, where  is the current coordinate time. When r and

is the current coordinate time. When r and  are constant,

are constant,  and

and  . The incremental proper time formula then becomes

. The incremental proper time formula then becomes

So for an observer rotating at a constant distance of r from a given point in spacetime at a constant angular rate of ω between coordinate times  and

and  , the proper time experienced will be

, the proper time experienced will be

As v=rω for a rotating observer, this result is as expected given the time dilation formula above, and shows the general application of the integral form of the proper time formula.

Examples in general relativity

The difference between SR and general relativity (GR) is that in GR you can use any metric which is a solution of the Einstein field equations, not just the Minkowski metric. Because inertial motion in curved spacetimes lacks the simple expression it has in SR, the line integral form of the proper time equation must always be used.

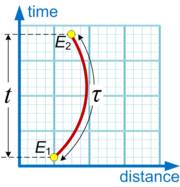

Example 3: The rotating disk (again)

An appropriate coordinate conversion done against the Minkowski metric creates coordinates where an object on a rotating disk stays in the same spatial coordinate position. The new coordinates are

and

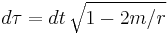

The t and z coordinates remain unchanged. In this new coordinate system, the incremental proper time equation is

With r, θ, and z being constant over time, this simplifies to

which is the same as in Example 2.

Now let there be an object off of the rotating disk and at inertial rest with respect to the center of the disk and at a distance of R from it. This object has a coordinate motion described by dθ = -ω dt, which describes the inertially at-rest object of counter-rotating in the view of the rotating observer. Now the proper time equation becomes

So for the inertial at-rest observer, coordinate time and proper time are once again found to pass at the same rate, as expected and required for the internal self-consistency of relativity theory[2].

Example 4: The Schwarzschild solution — time on the Earth

The Schwarzschild solution has an incremental proper time equation of

where

- t is time as calibrated with a clock distant from and at inertial rest with respect to the Earth,

- r is a radial coordinate (which is effectively the distance from the Earth's center),

- θ is the latitudinal coordinate, being the angular separation from the north pole in radians.

is a longitudinal coordinate, analogous to the latitude on the Earth's surface but independent of the Earth's rotation. This is also given in radians.

is a longitudinal coordinate, analogous to the latitude on the Earth's surface but independent of the Earth's rotation. This is also given in radians.- m is the geometrized mass of a central massive object, being m = MG/c2,

- M is the mass of the object,

- G is the gravitational constant.

To demonstrate the use of the proper time relationship, several sub-examples involving the Earth will be used here. The use of the Schwarzschild solution for the Earth is not entirely correct for the following reasons:

- Due to its rotation, the Earth is an oblate spheroid instead of being a true sphere. This results in the gravitational field also being oblate instead of spherical.

- In GR, a rotating object also drags spacetime along with itself. This is described by the Kerr solution. However, the amount of frame dragging that occurs for the Earth is so small that it can be ignored.

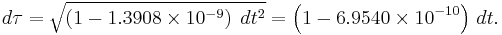

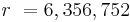

For the Earth, M = 5.9742 × 1024 kg, meaning that m = 4.4354 × 10 −3 m. When standing on the north pole, we can assume  (meaning that we are neither moving up or down or along the surface of the Earth). In this case, the Schwarzschild solution proper time equation becomes

(meaning that we are neither moving up or down or along the surface of the Earth). In this case, the Schwarzschild solution proper time equation becomes  . Then using the polar radius of the Earth as the radial coordinate (or

. Then using the polar radius of the Earth as the radial coordinate (or  meters), we find that

meters), we find that

At the equator, the radius of the Earth is r = 6,378,137 meters. In addition, the rotation of the Earth needs to be taken into account. This imparts on an observer an angular velocity of  of 2π divided by the sidereal period of the Earth's rotation, 86162.4 seconds. So

of 2π divided by the sidereal period of the Earth's rotation, 86162.4 seconds. So  . The proper time equation then produces

. The proper time equation then produces

This should have been the same as the previous result, but as noted above the Earth is not spherical as assumed by the Schwarzschild solution. Even so this demonstrates how the proper time equation is used.

See also

- Lorentz transformation

- Minkowski space

- Proper length

- Proper acceleration

- Proper mass

- Proper velocity

Footnotes

- ↑ Minkowski, Hermann (1908), "Die grundgleichungen für die elektromagnetischen Vorgänge in bewegten körpen", Nachrichten von der Königlichen Gesellschaft der Wissenshaften und der Georg-August-Universität zu Göttingen (Göttingen): 53–111, http://gdz.sub.uni-goettingen.de/no_cache/en/dms/load/img/?IDDOC=62931

- ↑ cf. R. J. Cook (2004) Physical time and physical space in general relativity, Am. J. Phys. 72:214–219

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![d\tau = \sqrt{\left [1 - \left (\frac{r \omega}{c} \right )^2 \right] dt^2 - \frac{dr^2}{c^2} - \frac{r^2\, d\theta^2}{c^2} - \frac{dz^2}{c^2} - 2 \frac{r^2 \omega \, dt \, d\theta}{c^2}}.](/I/c094563ca5b9e951687555f0c1844028.png)

![d\tau = \sqrt{\left [1 - \left (\frac{R \omega}{c} \right )^2 \right] dt^2 - \left (\frac{R\omega}{c} \right ) ^2 \,dt^2 + 2 \left ( \frac{R \omega}{c} \right ) ^2 \,dt^2} = dt.](/I/b2a48d1f97f8b8127593dfadc550faf7.png)